Data governance for democracy

Matt Prewitt

President, RadicalxChange Foundation

The existing data economy undermines the foundations of open societies: meaningful democratic participation, productive collaboration, broad distribution of benefits, and fair competition. Instead, we see power centralized in a handful of players, wasted potential, and rampant economic exploitation. Consider, for example, huge networks like Facebook and Amazon that capture the information of billions of people and place it in the service of a few shareholders’ narrow interests—when the very same technologies could be harnessed to drive shared wealth and responsible progress. What to do?

Divya Siddarth

Political economist and social technologist. She has worked with the RadicalXChange foundation, the Ostrom Workshop, Stanford's Digital Civil Society Lab, Microsoft, and Microsoft Research

Commentary

Data Governance for Democracy

Matt Prewitt and Divya Siddarth

September 23rd, 2021

Overview

The existing data economy undermines the foundations of open societies: meaningful democratic participation, productive collaboration, broad distribution of benefits, and fair competition. Instead, we see power centralized in a handful of players, wasted potential, and rampant economic exploitation. Consider, for example, huge networks like Facebook and Amazon that capture the information of billions of people and place it in the service of a few shareholders’ narrow interests—when the very same technologies could be harnessed to drive shared wealth and responsible progress. What to do?

Conventional thinking offers a choice between government-driven, top-down regulation of data use, or data management by loosely regulated, for-profit organizations with little public accountability. Neither of these approaches can succeed. Regulating data use, as experience with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation shows, will always be several years behind the moving-target concerns it seeks to address. On the other hand, the power of first-mover advantage and network effects mean that privately operated information networks will always tend to accrue monopolistic power, favoring narrow private interests at the expense of the public. Attempts to limit private abuses through fair competition will remain Sisyphean, because the massive potential gains from network scale will keep pushing toward consolidation.

A third way is emerging. Innovations in privacy-preserving techniques and tools for distributed data governance make feasible entirely new data-governance structures. At the heart of this vision is a new class of intermediary institutions that will be accountable to the democratically expressed interests of users and the public, rather than shareholders. These systems could allow businesses, governments, communities, and civil society to forge new digital infrastructures that would protect fundamental rights and involve citizens in meaningful decisions about data use, while also unlocking data’s huge potential to serve vital public interests in everything from medicine to combating misinformation.

The Problem

Data is core to our technical, sociotechnical, and economic systems; thus, data governance is core to democracy. However, the current data ecosystem leaves little room for meaningful democratic participation or productive collaboration between actors. The two existing paradigms for data governance are prescriptive, state regulation-focused systems and loosely regulated, market-focused systems in which private organizations have outsized influence. Both conventional systems operate under the untenable view of data as individual private property. In viewing data this way, these systems rely on individuals to address questions of privacy, fairness, and consent. While well-intentioned, this mistaken premise precludes the possibility of collectively addressing collective problems. Consequently, it often undermines any hope of protecting individual rights or of generating outcomes from data that will broadly benefit society.

Why is it a mistake to consider data the subject of individual decisions? Consider the case of genetic data. Under what conditions may I disclose my personal genetic data, which my family members also share? General data-use regulations cannot address this or the many similar problems in which data disclosure implicates third parties. The regulatory approach wrongly assumes regulators can abstractly describe the conditions under which two-sided consent suffices to justify an information transaction but, in this example, the question can only be answered by my family members, not by a regulator.

It is possible to imagine private organizations mitigating this problem by encrypting and anonymizing data more assiduously. However, such private solutions would inevitably exacerbate other issues. For example, Google’s proposed FLoC system, which would use massive amounts of data to let advertisers specifically target people by their behavioral characteristics without revealing to advertisers whom they were targeting, would help to maintain individual anonymity and reduce the amount of personal information that advertisers obtain through ad-serving technologies. However, on the downside, by leveraging the massiveness of Google’s network, FLoC would further entrench Google’s web dominance, making it even more costly for users and advertisers to leave, and thus further diminishing individual agency in the digital ecosystem.

The Solution

New data governance paradigms can shift the balance of power in our digital infrastructure toward democratically stewarded systems that optimize for shared benefit. To meet this challenge, businesses, governments, communities, and civil society must collaborate to build a robust new institutional layer for data governance.

Responsible and democratically accountable intermediary institutions acting as fiduciaries for pooled data are at the heart of this vision. These intermediaries would comprise a new class of regulated legal entity with special rights to represent the data interests of persons who entrust them to do so, balanced by specific fiduciary-style obligations to those persons. Such intermediary institutions could unlock massive public benefits while protecting individual and community choice. For example, they could facilitate responsible data sharing for needs as diverse as COVID-19 contact tracing or tracking carbon emissions. They could promote the sharing of research data between institutions, rapidly unlocking new strategic technologies and medical cures, allow for small-scale aggregation of financial data, which could help to modernize credit unions, and unleash new community financial tools, like group insurance.

Recent technical breakthroughs and policy advances can support the creation of data intermediaries that are technically manageable and democratically governable. For instance, privacy-preserving machine-learning techniques have made it easier for specific insights to be extracted from pooled data; and the ability to share particular insights instead of conveying whole datasets makes data more governable. Tools for distributed governance, like quadratic voting, could help larger numbers of people participate productively in the stewardship of new data intermediaries. Emerging proposals involving data trusts, consent aggregators in India, and data marketplaces in the EU provide a foundation from which to establish intermediary structures that both protect individual rights and optimize for the collective interest. Innovative data pooling for the public good is already occurring in advanced digital democracies like Taiwan.

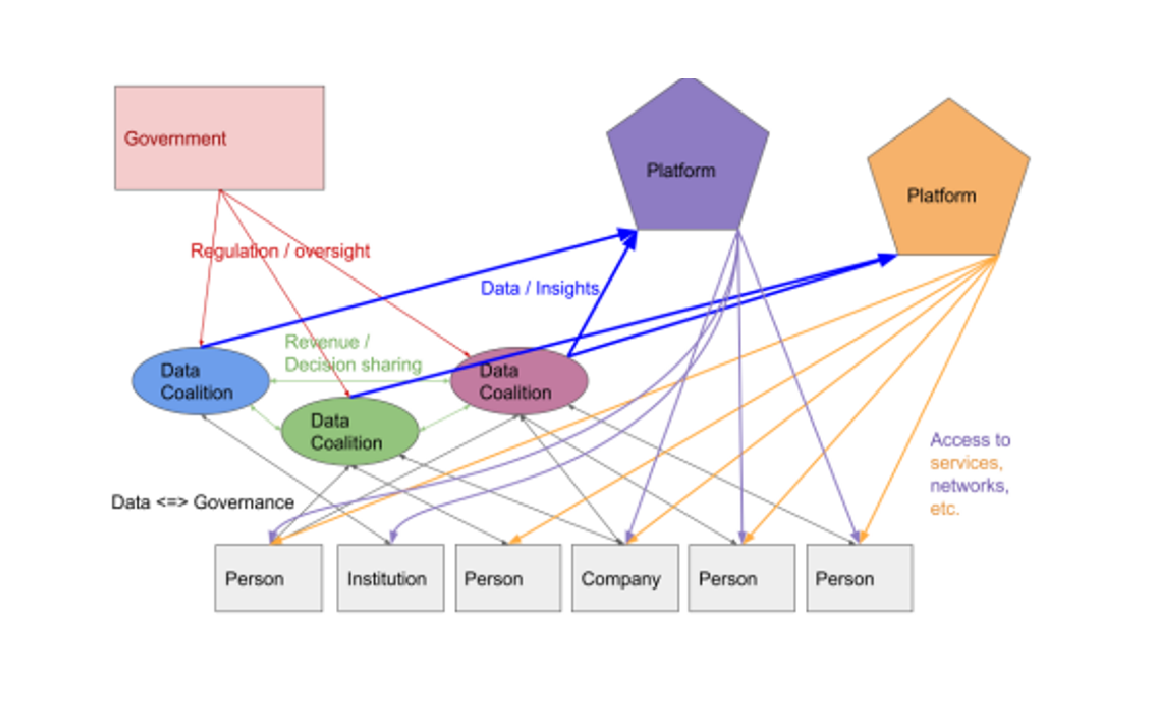

Figure 1. Proposed scheme of data governance using intermediaries. Legal persons assign data interests to intermediary data coalitions. Data coalitions, following democratic guidance from members, convey insights from their members’ data to platforms (service providers like Amazon or Facebook), and negotiate with the platforms on behalf of members. Platforms provide services to members of data coalitions. The government regulates data coalitions and arbitrates complex disputes involving overlapping data interests of members.

Designing Accountable Intermediaries

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to accountable intermediary structures, which must be context-specific and flexible by design. However, intermediaries should typically include the following:

● Transparent, non-discriminatory processes through which individuals and communities can understand, direct, and share in the benefits of their data.

● The ability to act flexibly in response to the needs of member individuals or institutions.

● Established mediation processes to address potential conflicts with other data intermediaries.

● Pathways for persons to exert democratic control over their data intermediaries, whether through legacy institutions like public agencies or novel governance structures such as decentralized autonomous organizations mediated by blockchain technologies.

● Underlying operating software that is non-proprietary and allows data to be easily downloaded and transferred between intermediaries, to minimize user lock-in.

● Pluralistic, polycentric power structures designed to incorporate public feedback and promote societal involvement.

● Fiduciary duty to members, guided by a strong code of ethics, much like that of doctors to their patients or lawyers to their clients.

Conclusion

The dysfunction in the current data economy is forcing a social, cultural, and technological phase shift in the way we manage information. Most conventional solutions to this challenge are inadequate because they are preoccupied with decisions either at the highest governmental level or at the level of the individual. A major new layer of information infrastructure is likely to emerge, facilitated by privacy-enhancing technologies and centering on a new class of powerful, democratically accountable intermediaries stewarding pooled datasets. This is the most attractive option, as it could preserve the fair competition fundamental to democratic societies. Correctly designed, this new layer of intermediaries will benefit societies and democracies by protecting our complex and varied interests in data while unlocking the massive social benefits that large-scale data sharing can provide.