Rebuilding European Bridges: Science diplomacy and the Ukraine-Russia conflict

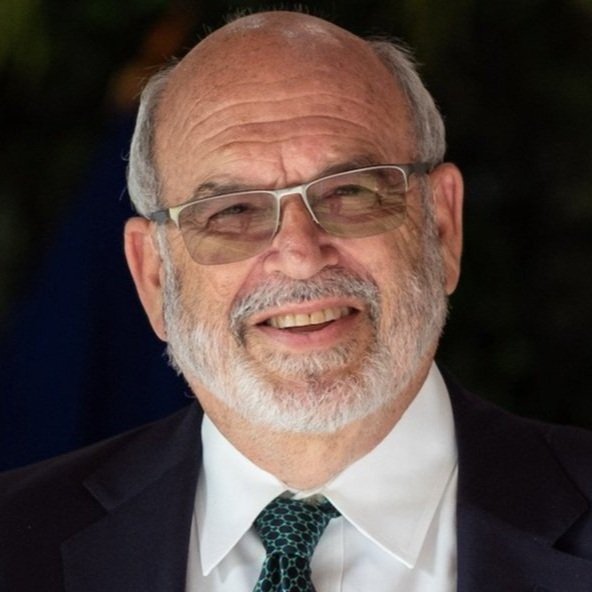

Luk Van Langenhove

Research professor

Brussels School of Governance

Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Eric Piaget

Visiting Research Fellow

United Nations University's Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies (UNU-CRIS)

7 June 2023

One can only hope that the war imposed by Russia on Ukraine will be brought to an end swiftly, that reconstruction of Ukraine as a sovereign state moves forward unimpeded, and that Russia, with its population of 140 million, will make earnest attempts to rectify its pariah status and re-join the rules-based international community.

When or if this will happen is not clear, but the EU should nonetheless be well prepared for the eventuality. This is true for all policy domains, but in this note we will focus upon the science and technology programmes of the EU and make some suggestions on how to use the instruments of science diplomacy for rebuilding the Ukrainian science system and reintegrating Russian scientists in the world science system, including the support of renewed scientific cooperation between Russia and Ukraine.

Before the War

The past two decades saw the EU roll out a series of instruments to strengthen scientific cooperation with both countries. Cooperation agreements in the field of science and technology were signed with Russia in 2001 and with Ukraine in 2002, which expanded already considerable collaborations in place since the end of the Cold War.

For Ukraine, scientific cooperation with the EU has been deepened through the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which, since 2004, has aimed to bolster security, stability, and prosperity in the countries on the EU’s periphery. One way to achieve that has been through increased cooperation in research, science, and innovation through several different mechanisms, such as funding for joint research projects and exchanges of scientists and researchers. The ENP also promotes the sharing of knowledge and expertise, as well as the development of research infrastructure and capacity-building in the neighbourhood.

Ukraine has also benefited by having access to Horizon 2020 (H2020) and European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) actions. According to the European Commission, Ukraine participated in 230 H2020 projects, involving 323 participants, and requested a total of €45.5 million in funding.[1] Energy, climate, and transport were the strongest areas of Ukraine-EU collaboration. In October 2021, Ukraine was associated with both the Horizon Europe and Euratom Research and Training Programme.

For Russia, which opted not to join the ENP, scientific collaboration was facilitated through one of the four EU-Russia Common Spaces: the Common Space on Research, Education and Culture. This opened the door to Russia to participate in H2020 as well. While significantly less than Ukraine, Russian projects gained €14.12 million funding through 139 H2020 grants.[2]

The largest sum, of €3.36 million, was awarded to the Kurchatov Institute for research on nuclear energy.[3] Russia was also involved in approximately 60-70 COST Actions annually.[4] The pinnacle of EU-Russian scientific cooperation occurred in 2014, which was dubbed the EU-Russia Year of Science. Hopes were high for a more integrated future. However, that was also the year that Moscow illegally annexed Ukraine, which dimmed the widespread optimism felt by many before.

While the EU imposed a formidable sanctions regime following Crimea, it stopped short of severing scientific ties like NATO did by cutting Russia out of its Science for Peace and Security Programme (SPS). Instead, the EU and Russia maintained a scientific bridge through the EU-Russia Joint Science and Technology Cooperation Committee, which provided a platform for regular dialogue and exchange of information on research activities and funding opportunities.[5]

During the War

On the 24th of February 2022, Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, unleashing horrific suffering on the Ukrainian people, violently eroding the rules-based international order, and nudging the world perilously close to a nuclear conflict. Instantly, the West imposed the first of several broad sanctions packages on the Russian Federation.

Scientific sanctions soon followed on the 4th of March, when the European Commission announced Russian organizations will no longer be eligible to partake in projects under the Horizon Europe programme.[6] Russian bodies were also removed from existing H2020 projects, Euratom, and Erasmus+. Member states moved along similar lines, cutting bilateral ties with Moscow in, inter alia, the scientific field. For example, on the day of the invasion, the German government instructed universities in the country to freeze ties with their Russian counterparts.[7]

Russian science was also forced to react. While a considerable number of Russian scientists opposed the war – as could be seen in an open letter signed by thousands of dissatisfied researchers, academics, and scientists – there were also strong signals of support for what was labeled the “special military operation”, reflected in a joint statement by Russian university rectors.[8] Western institutions cut virtually all ties with Russian counterparts, although individual connections were still allowed, and even encouraged in some cases. Nonetheless, due to reasons such as self-censorship, political animosity, or persecution, Western researchers have found it increasingly difficult to maintain individual ties with their Russian counterparts.

Meanwhile, the West’s scientific links with Ukraine have been significantly strengthened. On one hand, Western institutions opened their doors to Ukrainian researchers who were forced to flee their country, as can be seen in the European Research Area for Ukraine (ERA4Ukraine) portal and the May 2022 initiative of the Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the European University Institute (EUI) to relocate and employ Ukrainian researchers. On the other hand, the EU has doubled down on its efforts to support science within Ukraine. A Horizon Europe office is expected to open in Kyiv later this year, which will help Ukrainian researchers become more integrated into the €95.5 billion programme by supporting researchers, strengthening collaboration, and fortifying research and innovation networks.

The JRC has also deepened cooperation with Ukraine, such as in the fields of nuclear security, smart specialization, and technology transfer.[9] Then-Commissioner Mariya Gabriel summed up the impetus for this intensified cooperation well: “We need to protect and nurture Ukraine’s scientific knowledge and innovation capacity, as these will be key to rebuild their country. To bring Ukraine closer to the EU, we support its efforts towards integration into the European Research Area.”[10]

After the War

At the time of writing, the war in Ukraine shows little promise of ending soon. As the fighting passed the one-year mark, both Russia and Ukraine were preparing attacks to deliver decisive blows to the other side. As the West steps up its armaments to Kiev, Russia fills its depleting ranks with civilians and convicts. An increasingly desperate Putin may consider filling his hitherto empty threats of a nuclear strike. There are many unknowns in this unfolding tragedy; making predictions with certainty is a fool’s errand.

However, with history as a guide, it is safe to assume that this war will end one day. Every war fought in the past, no matter its duration and degree of brutality, eventually came to its end. When this war follows that trend, it is important to think about how wounds can heal, and how bridges can be rebuilt. For the purpose of this note, we will look at this through science diplomacy, and how the EU can play an active role in delivering a sustainable peace through science.

Science diplomacy can be used to build bridges between countries that have strained political relations. It can be a powerful tool for fostering collaboration and mutual understanding, even between countries that have icy political relations and a violent history. Funding for joint research projects and scientific exchanges are some ways science diplomacy can help to (re)build bridges and promote dialogue between countries. Of course, to do this vis-à-vis Ukraine and Russia, there will need to be an appetite for rapprochement. As it stands, little desire for that exists between the parties. However, scientific cooperation in projects of shared concern could constitute the small steps towards a wider phase of rapprochement.

Science diplomacy can also be used to promote shared values and policies, such as the importance of open and transparent research, in international interactions. This can help to create a common ground for collaboration and can foster trust and mutual understanding between countries, as well as serve as the watershed for ushering Western values into non-like minded states.

Addressing global challenges is another key aspect to consider in the post-conflict situation. Science diplomacy addresses a wide range of global challenges, such as climate change, pandemics, and natural disasters. The promotion of international collaborations on scientific research and technology development can help to find solutions to these challenges and improve the lives of people around the world. Using this as a banner can hardly be controversial, so long as the science does not have a dual-use nature, or other hard power benefits that sustain belligerence.

In a similar sense, science diplomacy can be used to support sustainable development. Science and technology can play a crucial role in supporting sustainable development and the SDGs, such as by developing innovative technologies for clean energy and sustainable agriculture. Science can be a vessel to promote international collaboration on these issues and to support the development and deployment of sustainable technologies in Russia and Ukraine. Considering one of the greatest globally tangible impacts of the war has been on the world’s food supply, and that the Black Sea Grain Initiative has been one of the few diplomatic breakthroughs during the conflict, agriculture could be fertile ground upon which to focus.

Science diplomacy is also a way to foster innovation and economic development. Both Russia and Ukraine will have their economies in tatters after the war, which is why this is an important consideration. Economic recovery needs innovations and science. An equivalent of the Marshall plan after the Second World War will be needed and it should envisage support to science, technology, and innovation.

Civil society empowerment is another factor to consider. Science diplomacy is typically focused on interactions between states, but it can also be used to engage with non-state actors, such as NGOs, research institutions, and private companies. By fostering collaboration and exchange of ideas with these actors, science diplomacy can help to promote innovation and address global challenges in new and creative ways. In the context of Russia and Ukraine, it could be a gust of wind into the sails of civil society in these countries (particularly in Russia, where civil society has been increasingly under attack).

Most importantly, however, science diplomacy can be used to promote peace and security, such as by developing innovative technologies for conflict resolution, peacekeeping, and disarmament. Science diplomacy, if done correctly, can promote international collaboration on these issues and foster mutual understanding and trust between countries. Just look at SESAME, and other examples that use science as a means of cooperation between parties with turbulent political relationships (e.g., India and Pakistan and the joint work conducted under the Indus Waters Treaty; or countries of former Yugoslavia working together in the framework of SEEIIST).

Conclusions

Once hostilities between Russia and Ukraine cease, tensions are expected to continue while the situation on the ground remains fragile. This affects the EU, as an unstable neighborhood causes problems such as increased migration and risk of political extremism. Within that context, a strategic science diplomacy action is desirable to mobilize scientific and technological research potential. By strengthening interactions between scientists from Ukraine, Russia, and the EU, it can be hoped that relations between the three partners can be improved.

There are three major areas of societal reconstruction where science diplomacy can play a decisive role. The first one is to leverage science to enhance economic reconstruction. This can be achieved by building infrastructures for science that directly support economic productivity and by implementing measures to combat brain drain. In this way, science diplomacy acts as a facilitator for economic reconstruction by fostering an environment that nurtures scientific and technological advancement. This involves building infrastructures for science and measures to combat brain drain.

A second major goal is to construct resilient structures and opportunities for scientific collaboration between Russian and Ukrainian scientists. The premise is that trust may develop over time but should not be the central objective. The key is to provide an arena where differences can be set aside in the name of scientific progress. The EU, being a mediator in this scenario, has a vital role to play.

Thirdly, the EU, as a scientific powerhouse, needs to bolster its bilateral and trilateral cooperation with both Ukraine and Russia. This will create an interconnected scientific community resilient to political fluctuations. Implementing these three policies simultaneously will be a challenge, but the EU has good reasons to invest in such an endeavor: it will contribute to stability at its borders, and it will help generate the support needed to develop its ambition of maximizing the mobilization of science towards global challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and nuclear security.

Strategic EU science diplomacy action on Ukraine and Russia should start from a set of strategic goals that can be realized through programmatic actions. To ensure a rapid operationalization, existing instruments should be used where possible.

The following strategic goals could be considered by the EU:

Contribute to the re-building of Ukraine’s science system.

Contribute to the maximal integration of Ukraine’s science system into the ERA (European Research Area).

Support and encourage collaboration between Russian and Ukrainian scientists, especially on the global challenges humanity faces.

Contribute to the re-integration of the Russian science system into the global science system, and strengthen collaboration between Russia and the EU on a case-by-case basis aimed at tackling global challenges.

Combat the expected scientific brain drain from Russia and Ukraine to the EU.

Support and coordinate EU Member State initiatives towards scientific and technological collaboration with Russia and Ukraine.

Science diplomacy, while potent, is not a magical cure-all for the pursuit of peace and prosperity. It does, however, serve as a fundamental driver in the dynamics of international relations: fostering cooperation, fueling competition, and at times, enabling domination. Harnessing cooperation and ensuring it does not give rise to dynamics that could threaten peace and exacerbate tensions is key in this case. Today's reality necessitates acknowledging that major challenges, such as climate change, are a collective burden, too immense for any single state to tackle alone. We are past the era where bystanders can be tolerated. Every state, regardless of size, alliances, or historical enmities, must participate in a global mobilization of science that promotes openness and values collaboration for addressing shared challenges.

In his recent interview with The Economist, Henry Kissinger articulated that lasting peace in Europe requires two significant shifts in perspective. The first is for Ukraine to become fully integrated into the Western security architecture. The second “is for Europe to engineer a rapprochement with Russia, as a way to create a stable eastern border.” [11] Science may very well be the best place for such a rapprochement to start. From our standpoint, this picture transcends political landscapes. The need to support Russian and Ukrainian scientists in rebuilding their capacities should be perceived not as a regional issue, but as an opportunity for global cooperation, a step towards mobilizing science to confront the overarching challenges that face humanity. This is a path we should not only consider, but actively pursue.

References

Research and innovation. (2022). Ukraine. [online] Available here. [Accessed 13 Dec. 2022].

Nishat (2022). EU stops all Horizon Europe funding going to Russia. [online] Open Access Government. Available here. [Accessed 13 Dec. 2022].

Ibid.

Sheridan, S. (2020). COST at the EU-Russia Joint Science & Technology Cooperation Committee - COST. [online] COST. Available here. [Accessed 15 Dec. 2022].

European External Action Service (2021). EU-Russia Joint Science and Technology Cooperation Committee met via video conference. EEAS Website. Available here. [Accessed 14 Jan. 2023].

European Commission (2023). Press corner. Available here. [Accessed 14 Jan. 2023].

Matthews, Naujokaitytė & Zubașcu (2022). German universities told to freeze ties with Russia in retaliation for invasion. Science Business. Available here. [Accessed 26 Jan. 2023].

O’Malley (2022). Russian Union of Rectors backs Putin’s action in Ukraine. University World News. Available here. [Accessed 2 Feb. 2023].

European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (2023). Ukraine, support for researchers and innovators. Publications Office of the European Union. Available here. [Accessed 4 Feb. 2023].

Ibid.

The Economist (17 May 2023). Henry Kissinger explains how to avoid world war three. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2023/05/17/henry-kissinger-explains-how-to-avoid-world-war-three

Sir Peter Gluckman

President, International Science Council

Van Langenhove’s and Piaget’s essay raises a number of important issues and realities. State-funded science and science diplomacy are inherently political. Science is funded to develop a nation’s knowledge capital and for it to have impact on economic, security, environmental and social outcomes. Science diplomacy has the primary goal of advancing a nation’s diplomatic interests. These may be either directly so in generating soft power, influence or direct economic advantage or relate to issues of the global commons, where nations recognize that it is in their self-interest to collaborate with other nations on issues such as climate change or biodiversity or in the oversight of ungoverned spaces such as the Antarctic, space, or the ocean (Gluckman et al. 2017). In the case of the Ukraine war, how Western-allied nations have acted reflects these realities and the conflicting values in play.

Many academics, at least in areas outside the security domain, would like to avoid these realities and focus on the ideal that science is free from political values. But all scientists are members of their societies, and their institutions are similarly embedded. This creates constraints. Thus, while some brave individual Russian scientists were able to protest the conflict, their institutions were, as state institutions without full autonomy, unable to do so.

We have seen in the decisions made by the Western alliance a dominance of direct national interests being in play, thus leading to the disruption of state funded research partnerships. But the disruption is not absolute – for example, cooperation in space continues to some extent and many individual science partnerships continue. The key issue is whether the disruption is interfering with critical commons research – for example in sustainability and climate related data collection.

In the first cold war, science was extensively used to maintain informal relationships between the two superpowers (e.g. Pugwash conferences) and indeed some notable successes of science diplomacy occurred despite the tension: the formation of the IPCC and the Antarctic Treaty (and the preceding International Geophysical Year) and the founding fo the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis. But this all happened in the absence of a direct hot war between the parties. The key questions are firstly, when will the conflict in Ukraine resolve into a cold war and secondly, what are the implications of a more complex multipolar geostrategic world rather than the bipolar world first cold war.

The International Science Council (ISC) as a non-governmental body was able thus to both condemn the war but did break relations with any party. It has been heavily involved in the issues of displaced scientists and in discussions about the post-conflict science system of Ukraine. But it sees its key role in science diplomacy to be, as was its predecessor International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), a key conduit between scientists and scholars on both sides of the conflict once the hot war subsides. Rebuilding trust and understanding in political terms is hard, but science is a universal language and there are many places where it can be used to rebuild trust and understanding.

P.D. Gluckman, V. Turekian, R.W. Grimes, and T. Kishi, “Science Diplomacy: A Pragmatic Perspective from the Inside,” Science & Diplomacy, Vol. 6, No. 4 (December 2017) http://www.sciencediplomacy.org/article/2018/pragmatic-perspective

Dr. Henry Huiyao Wang

Founder and President of Centre for China and Globalization

In light of world’s frustration with the seemingly endless Russia-Ukraine war, scholars Luk Van Langenhove and Eric Piaget have provided an appealing solution: science diplomacy. China may disagree with Western countries on how to resolve the issue in many ways, causing a great deal of confusion and distrust, but this has the possibility of working. It is such an innovative and practical approach that we should at the very least try.

From COVID-19 to climate change, more than ever before, society needs to unite in the face of mounting crises and challenges. However, issues like anti-globalization, inequality, and rising geopolitical friction have hindered the pace and scale of human cooperation. Science diplomacy can examine social problems from a scientific perspective, address social disputes through scientific means, and enhance cooperation based in scientific concepts, thus more effectively protecting society.

Jan Marco Müller

Coordinator for Science Diplomacy and Multilateral Relations,

DG Research and Innovation, European Commission

In their article, Luk Van Langenhove and Eric Piaget identify the paradigm shift in Science Diplomacy catalysed by the unlawful Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Following a comprehensive review of the history of scientific relations of the European Union to both Russia and Ukraine before and after the invasion, they propose the practice of Science Diplomacy to build bridges through promoting shared values and principles, addressing global challenges together by supporting sustainable development, fostering innovation and economic development for the reconstruction of Ukraine, engaging with civil society, and helping to build peace.

It is true that Science Diplomacy offers powerful tools to implement such roadmap back into a future of mutually beneficial scientific collaboration proposed by the authors. However, Science Diplomacy also needs to learn the lessons of realpolitik, as can be demonstrated by the scientific sanctions imposed upon Russia by the EU and its Member States as well as other partners, while simultaneously enhancing scientific cooperation with Ukraine. Scientists around the world need to acknowledge that in the current times of rapid geopolitical and scientific-technological change, research and innovation have become (again) game pieces on the geopolitical chessboard, not only in our relationship with Russia. One might deplore this, but it is a fact hard to ignore.

Without doubt, Russia will remain our – and Ukraine’s – neighbour, regardless of the outcome of the current horrific conflict, which will someday come to an end. Therefore, I agree with the authors that the maintenance of people-to-people contacts to scientists sharing our values remains indispensable to stay connected with civil society and plant the seeds for a post-war era, in which science diplomacy can be used to build peace and prosperity in the region. This said, a re-integration of Russia in the world science system is still a far fetch and the trust lost in Russian state actors will take a very long time to rebuild, if ever.

Disclaimer: The views set out in this text are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission.

Claire Mays

past co-chair of the EU Science Diplomacy Alliance

Luk Van Langenhove and Eric Piaget provide a wealth of valuable information regarding the state of scientific collaboration between the European Union and its Eastern Neighborhood prior to the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Their statement raises an important perspective on pathways back to science collaboration after the war. We appreciate the authors' realism in surveying the many science diplomacy mechanisms and opportunities for restoring cooperation between scientists after belligerence has opposed them. An even stronger call on realism may be made: trust is a desirable co-benefit of science diplomacy, but science diplomacy should aim for safe and effective means for collaboration which can withstand belligerence and be sustainably restored after such shocks. In this way Van Langenhove and Piaget’s reflection on rebuilding European bridges with Russia and the Ukraine may offer a wake-up call for Europe in facing global challenges. Science diplomacy of course is needed to foster transnational approaches to the protection of humanity’s shared interests. Moreover, the violent rupture introduced by Russia focuses attention on the need for fireproofing bridges. Science diplomats’ continuing reflexivity may serve our resiliency in the face of longer-burning and less visible fires.

Irek Suleymanov

International Cooperation Adviser

Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (International Intergovernmental Organization) in Dubna, Russia